While reading “In Defense of Lenin” by Alan Woods and Rob Sewell, I noticed that Lenin constantly monitored the number of strikes occurring in Russia each year. For him, these statistics acted as a thermometer of the mood of the working class, almost as indicators of the dialectical changes the population was undergoing.

At that time, it was a revolutionary period. Russia had experienced the 1905 Revolution, which unfortunately did not fully materialize. The book reveals how meticulous Lenin was with his data, treating Marxism and the dialectical method as true sciences.

In Brazil, we have the habit of believing that we are a people different from the rest of the world. If you enter a conversation among middle-class circles, you’ll find numerous references to the supposed “cunning” and passive nature of our people. In the mainstream media, we won’t find a single reference to workers’ uprisings against the ruling class.

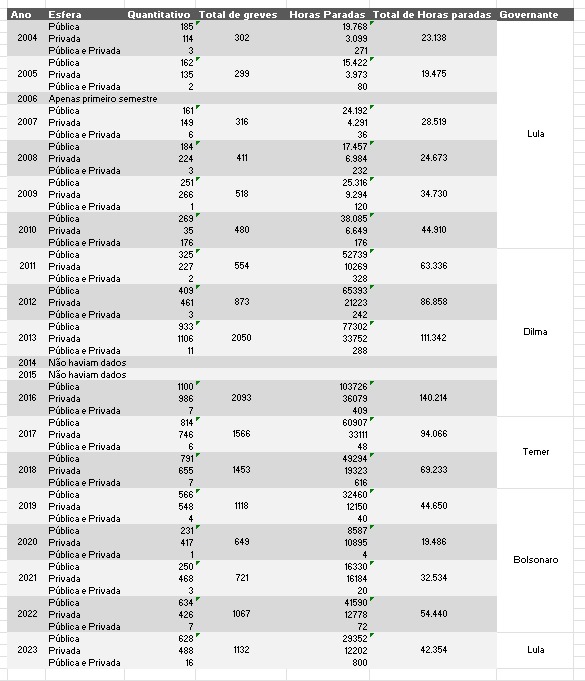

During my research, I found information on the website of DIEESE (Inter-Union Department of Statistics and Socioeconomic Studies), an institution created by Brazilian trade unions with the aim of developing research related to the world of work. According to this entity, which appears to have a solid reputation, we can establish the results of the Brazilian thermometer.

The best way to analyze the data is through a comparative chart between the years. Unfortunately, it was not possible to find data for years prior to 2004 and for the specific years of 2006, 2007, and 2015.

In general, the chart shows us that until 2011, there wasn’t significant growth in the number of strikes in Brazil. Starting from 2012, however, there was exponential growth, most likely due to the inflationary pressures the country was experiencing at that time, in addition to the media campaign for the ousting of then-president Dilma Rousseff. The data shows that the maximum peak was reached precisely during the final year of her government, decreasing gradually until 2020 and then registering an increase since then. The relatively low number of strikes during 2019, 2020, and 2021 most likely refers to the period of the COVID-19 pandemic that the world was going through.

In 2017, the country also underwent a labor reform that probably demotivated workers from claiming their rights, as they felt less secure. This time was also marked by low economic incentives, and significant public incentives were created, such as a substantial increase in the Bolsa Família program—the famous distribution of money from a helicopter. These policies kept the economic sector minimally stimulated.

This period was also marked by a strong reaction from the Bolsonaro government, which was much more rigid regarding unions, ending their funding and implementing a repressive apparatus against social movements.

Even with all this, the temperature began to rise again at the end of the Bolsonaro era, with a 48% increase in strikes in his last year in office. Incredibly, despite the disincentives mentioned above, the number of hours stopped due to strikes showed an even more significant increase of 67%, informing us that there was an increase in quantity but that the strikes also became heavier and more prolonged.

The Lula government is not starting very well. It is usually more natural for workers to go on strike under leftist governments because they feel more protected, but the predominant factor is that their quality of life does not seem to be improving. This latest Lula government is a centrist government composed of both left and right forces, not leaving much room for improvements in the working conditions of workers.

As a prognosis for the coming years, everything leads us to believe that there will be an increase in the number of strikes. The global economic situation to which Brazil is subjected is rapidly deteriorating, with protectionist movements spreading around the world. The scenario ahead is not the best for the global economy.

Let’s watch…

Deixe um comentário