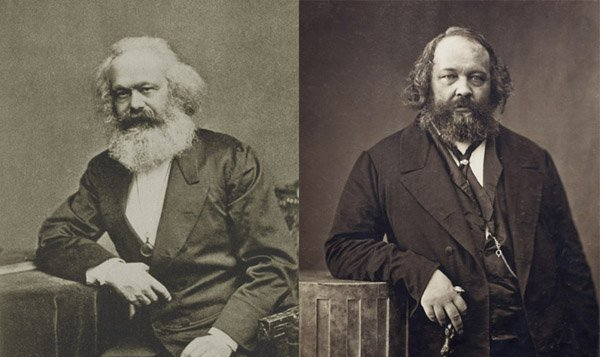

Resumo do Capitulo – Marx vs Bakunin, do livro The Ideas of Karl Marx – Alan Woods

Este capítulo examina o conflito entre Karl Marx e Mikhail Bakunin no seio da Primeira Internacional, revelando divergências fundamentais entre o marxismo e o anarquismo. Marx defendia a centralização da luta política e a criação de um partido operário para a tomada do poder, enquanto Bakunin rejeitava a ação política e pregava a destruição imediata do Estado e das instituições capitalistas — uma abordagem marcada por desorganização e fracassos práticos.

Bakunin ingressou na Associação Internacional dos Trabalhadores (AIT) em 1868, tentando logo formar uma facção anarquista chamada Aliança Internacional da Democracia Socialista. Seu objetivo era enfraquecer a liderança de Marx no Conselho Geral e impor suas ideias. Ele protagonizou intrigas contra o Conselho e violou regras democráticas, acusando Marx de autoritarismo, embora liderasse sua própria facção de forma ditatorial. Suas críticas incluíam ataques nacionalistas e até antissemitas.

Um dos episódios mais graves foi sua aliança com Sergei Nechayev, envolvido em assassinato e fraudes. Bakunin acobertou essas ações, prejudicando a reputação da AIT. Também encabeçou revoltas mal planejadas, como em Lyon, que fracassaram por falta de organização.

Bakunin propôs medidas utópicas, como a abolição imediata da herança, ignorando as condições materiais. Marx considerava isso impraticável, pois alienaria pequenos proprietários, aliados potenciais do proletariado. Ele argumentava que transformações como essa só seriam possíveis quando a base econômica permitisse.

A recusa de Bakunin à política formal deixava a classe trabalhadora vulnerável à influência burguesa. Para Marx, isso era um erro grave, pois a independência política do proletariado era essencial para a revolução.

No Congresso de Haia (1872), Bakunin e seu seguidor James Guillaume foram expulsos da Internacional. Engels classificou o bakuninismo como uma seita movida por ambição pessoal e métodos desleais. A decisão foi crucial para preservar a integridade revolucionária da AIT.

Marx defendeu o centralismo não como imposição autoritária, mas como necessidade histórica. Sua vitória consolidou o marxismo como corrente hegemônica do socialismo, enquanto o anarquismo permaneceu marginal e sem papel relevante nas grandes revoluções do século XX.

Deixe um comentário