Entrism was not an isolated invention but rather a dialectical evolution of revolutionary tactics. From Lenin to Trotsky and later Ted Grant, it transformed from a temporary tool into a more refined strategy adapted to concrete realities.

Lenin never formulated Entrism as a separate tactic, but his strategy of revolutionary organization already suggested the necessity of working within mass organizations. Unlike the later scenario developed by Trotsky and Ted Grant, there were no parties at that time with reformist tendencies toward capitalism. His strategy was focused on achieving objective results, demonstrating the need to be where the working class was organized. Some of the actions he advocated included intervention within trade unions, participation in the Duma to propagate revolutionary ideas, and tactical flexibility, understanding that revolutionaries must know how to operate both legally and clandestinely, depending on the moment.

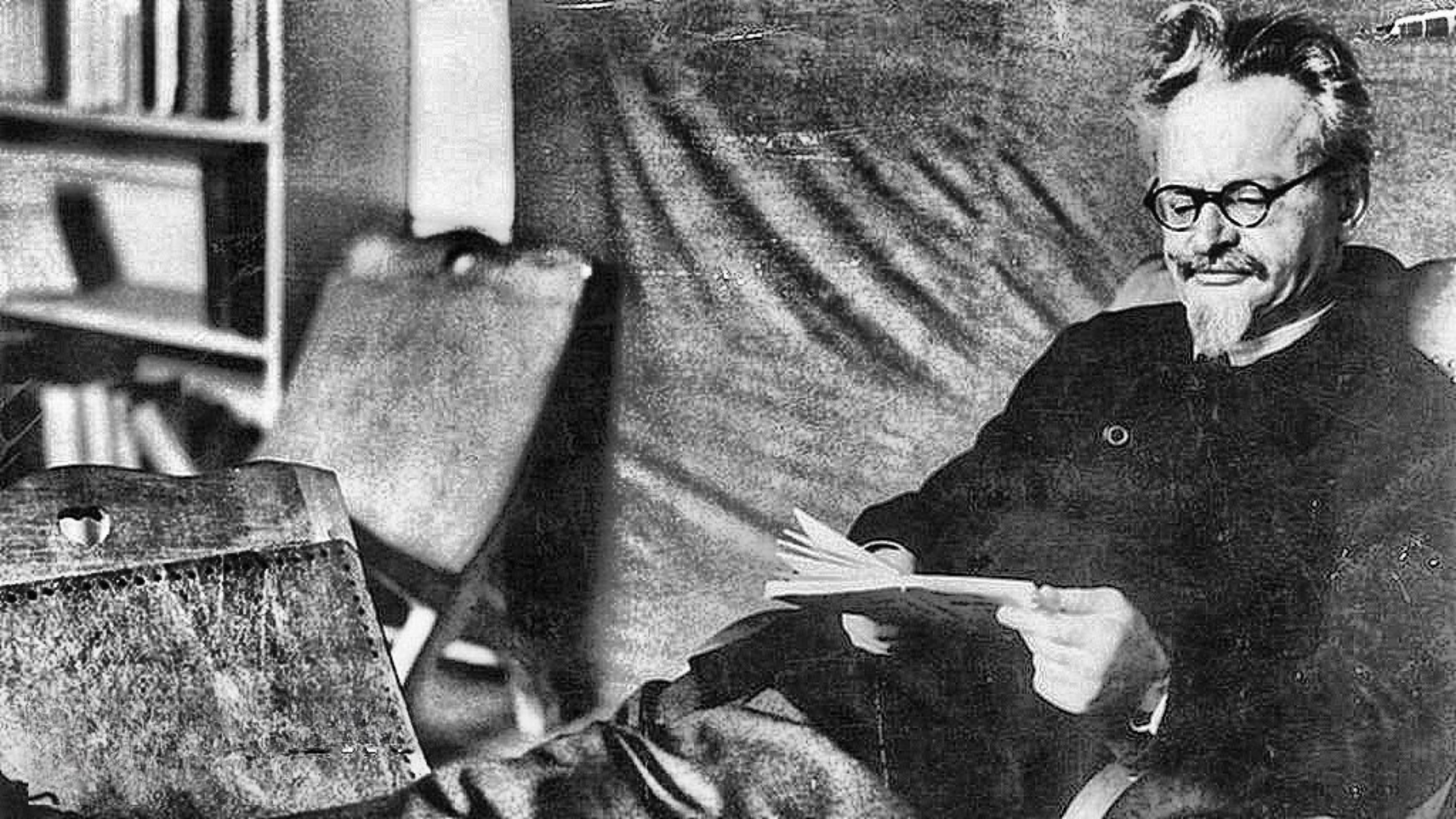

The scenario Trotsky faced was quite different since the revolution had been overtaken by Stalinist bureaucratization, and the Third International (Comintern) had fallen under its control. At the same time, large social-democratic and labor organizations were growing, still serving as references for workers, while the rise of fascism created an urgent need for a more effective method to win over sectors of the working class.

Trotsky proposed that Trotskyists enter reformist workers’ parties. The idea was to win over the most advanced sectors of the working class to the revolutionary program, avoid the sectarian isolation of Trotskyists, and take advantage of the internal crises of reformist parties to influence their base. This became known as “Classic Entrism,” but it was conceived as a temporary tactic.

Under Ted Grant, conditions had changed significantly. The establishment of Stalinism in the international communist movement had prolonged reformism, and the impact of World War II further shaped the landscape. Due to the lack of short- and medium-term prospects, he developed a long-term strategy, introducing some innovations. These included focusing on large workers’ parties (such as the British Labour Party) instead of small left-wing sects, recognizing that reformism would not collapse on its own since reformist leaders had a strong bureaucratic apparatus, and gaining a deeper understanding of dialectics within mass parties and their internal contradictions.

Within the same party, there could coexist a bureaucratic and conciliatory leadership that constantly betrayed workers’ hopes, a more radicalized working-class base that, due to these betrayals, became more open to radical ideas, and centrist tendencies that wavered depending on the circumstances.

Entrism is not simply about “entering and waiting.” It requires a dialectical understanding of the party as a battleground of different tendencies. The key is to identify internal contradictions and exploit them, acting as a revolutionary pole within the organization without isolating oneself from the base, and knowing the right moment to act—whether to gain influence or to leave and build something new.

Leave a Reply